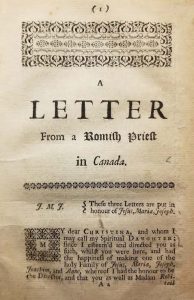

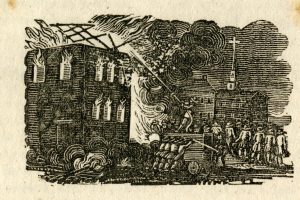

Catholic University’s Special Collections Department has a vast quantity of documents which encompass the sentiment of Anti-Catholicism in America that spans from colonial times to the dawn of the twenty-first century. Our rare books collection includes eighteenth century works such as Letter from a Romish Priest in Canada to one who was taken captive in her infancy, and was instructed in the Romish faith by Francois Seguenot (1729) and A specimen of a book, intituled, Ane compendious booke, of godly and spiritual sangs,collectit out of the Scripture,with sundrie of other ballates changed out of prophaine sangs, for avoyding of sinne and harlotrie by Robert Wedderburn (1765). Nineteenth century examples include Popery: the foe of the church and of the Republic and Popery Unmasked, while the twentieth century contributes entries such as Priest Baiting and Jesuits: Religious Rogues. Additionally, we have archival documentation on the 1834 burning of the Ursuline Convent in Massachusetts, as well as Anti-Catholic Literature that was collected during the 1928 presidential campaign. The Catholic response to counter this bias included a newspaper column titled Catholic Heroes of the World War, 1928-1933, and the National Council of Catholic Men’s Catholic Hour radio and television programs.

Anti-Catholicism in America grew from the attitudes of Protestant immigrants who were fleeing religious persecution by the Church of England whose doctrines aligned with the Roman Catholic Church. Anti-Catholic rhetoric such as the Biblical Anti-Christ and Whore of Babylon was derived from the theological heritage of the Reformation which criticized the perceived excesses of Catholic clerical hierarchy in general and the Papacy in particular. Theological differences were compounded by secular xenophobia and feelings of nativism towards these increasing numbers of Catholic immigrants, particularly those coming from Ireland and later, eastern and southern Europe and Latin America. Catholic support for the American Revolution helped alleviate notions of the inherently treasonable nature of Catholicism. George Washington staunchly promoted religious tolerance as a means of public order. He suppressed anti-Catholic celebrations in the Army while our reliance on Catholic France and Spain for military aid helped reduce anti-Catholic rhetoric. By the 1780s, Catholics were extended legal tolerance in many states and the anti-Catholic tradition of Pope Night was discontinued.[1]

Anti-Catholicism peaked in the mid nineteenth century as Protestant leaders accused the Church of being an enemy to republican values. The Catholic Church’s silence on the subject of slavery also raised the ire of northern abolitionists. In 1836, Maria Monk was published to great commercial success. It was the most prominent of many scurrilous pamphlets that were published even though it was later revealed to be a fabrication. Numerous supposedly former priests and nuns went on an anti-Catholic lecture circuit telling lurid tales that usually involved sexual depravity and dead babies. Intolerance again exploded in 1834 when a mob burned the Ursuline convent in Charlestown, Massachusetts. The resulting nativist movement morphed politically into the Know Nothing Party, which unsuccessfully backed former president Millard Fillmore as its presidential candidate in 1856. But during the Civil War, widespread enlistment of Irish and German immigrants into the Union Army, as well as the dedicated service of priests acting as chaplains and nuns serving as nurses, helped demonstrate Catholic Patriotism.

After the Civil War ended, tensions were again raised by a proposed amendment to the Constitution which stipulated that no public money could be used to support any sort of religious school. Although President Ulysses S. Grant supported this amendment, it was defeated in 1875. However, it was used as the basis for dozens of successful state amendments that prohibited using public funds for parochial schools. The early 20th century brought about a new appreciation of Catholicism, especially in western states where Protestantism had not yet become deeply ensconced. Examples of this show how California celebrated the history of Spanish Franciscan missions, which later became popular tourist attractions and in the Philippines, which was newly occupied by the United States, Catholic missionary efforts were praised. Catholic mobilization efforts during World War I by the National Catholic War Council and the Knights of Columbus were also appreciated by many non-Catholic Americans.

Nevertheless, anti-Catholicism continue to rage in the interwar years as the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) continued to argue that Catholicism was incompatible with democracy and that parochial schools prevented Catholics from becoming loyal Americans. In 1922, Oregon voters passed the Oregon School Law, which mandated attendance at public schools. The law outraged Catholics and in 1925 the Supreme Court declared it unconstitutional. In 1928, Democrat Al Smith of New York became the first Roman Catholic to gain a major party’s nomination for president. Many Protestant ministers warned that the nation was at risk because Smith would take secret orders from the Pope. Another strike against Smith was his opposition to Prohibition, which had widespread support in rural Protestant areas. Despite his loss, Democratic voting surged in large cities as ethnic Catholics, including recently enfranchised women, went to the polls to defend their religious culture. Catholics made up a major portion of the New Deal Coalition that Franklin D. Roosevelt enacted four years later and which continued to dominate national elections for decades.

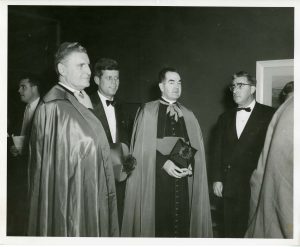

The Second World War and the Holocaust brought religious tolerance to the fore. Despite Eleanor Roosevelt’s feud with the Archbishop of New York, Francis J. Spellman, over federal aid to Catholic schools, the 1950s promoted a unified front against communism. National leaders appealed to the common values of Protestants, Catholics, and Jews alike. The so-called ‘Catholic Question’ continued to be a key factor that affected voting in the 1960 Presidential Campaign. To allay Protestant fears, Catholic John F. Kennedy, who narrowly won the office, kept his distance from Church officials and publicly stated “I do not speak for my Church on public matters—and the Church does not speak for me.”[2] After 1980, historic tensions between evangelical Protestants and Catholics dissipated as the two groups often saw themselves allied in regard to contentious social issues like abortion and gay marriage. By 2000, Catholics made up about one half of the Republican Coalition with the rest being comprised of a large majority of white evangelicals.

Please see the new Catholic University of America Library Research Guide on Anti-Catholic Resources which are held in our Special Collections and was created by William J. Shepherd and Amanda Bernard.

[1] Pope Night was an anti-Catholic holiday celebrated annually on November 5 in colonial America. It had evolved from Guy Fawkes Night in Great Britain that commemorated the failure of the Gunpowder Plot of 1605 by prominent Catholics to blow up the British Parliament. The rowdy celebration included drunken street brawls and the burning of the Pope in effigy.

[2] NPR Web site at https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=16920600