Guest blogger, Professor Árpád von Klimó, of The Catholic University of America History Department teaches Modern European and World History at the University. He has done research in different fields of Modern and Contemporary European history. Most recently, he has edited the Routledge History of East Central Europe (together with Irina Livezeanu) and published two monographs: “Hungary since 1945” (Routledge, 2018) and “Remembering Cold Days. The Novi Sad Massacre, Hungarian Politics and Society since 1942” (Pittsburgh UP, 2018).

His research on Father Dennis is part of a broader project related to the history of the University’s History Department. He sees this history as a mirror of the past of an institution that has always profited from a fruitful tension between church and world, between priests and laymen. This story has not been told yet but this project seeks to tell it, in the process providing us with profound insights into the identity of the University, knowledge essential for its future. Since 2015, student apprentices, faculty, and archivists have begun to compile, sort, publish, and analyze archival materials related to the department of history, its professors and students. This project is part of a new program of undergraduate apprenticeships in history (course HIST 494) in which students learn practical research, analytical, editorial and publication skills. Throughout this course, students learn how to manage unexplored mines of “big data,” to hone research and writing skills, and in the process gain insights into how many generations have experienced life and learning on this campus.

***

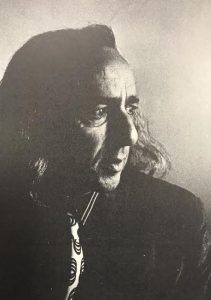

In the 1971 yearbook of The Catholic University of America (the University was informally referred to as “C.U.” at the time), a quotation accompanied the photo of Jesuit Father George T. Dennis, representing the History Department:

“The Speech and Drama Department represents about all that the rest of the city knows about CU. The University plays little or no role in the development of the community, yet it has facilities, leadership potential, and a great deal more to offer. ‘Neutrality’ is only the position of some administrators and, as is fairly obvious, does not represent the feeling of the University’s faculty or students. If the University does not loudly let its real stand on vital issues be known, it might as well relocate to some remote spot on the planet.”[1]

Father Dennis spoke about the necessity and duty of the University to be present in the District and to be actively engaged in helping to solve its political and social problems. These were immense after the riots and political turmoil of the Vietnam Years and in the wake of the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy. He would do his part, teaching urban youth for many years, while teaching Byzantine and Medieval History and doing research as a renowned scholar. Obituaries in The Catholic Historical Review and The Dumbarton Oaks Papers have talked about his scholarly achievements and mentioned his activities with urban youth of Washington, D.C.

George T. Dennis was 44 years old when he came to Catholic University in 1967 from Loyola University, Los Angeles, to work as editor of the Corpus Instrumentorum Inc., while teaching Byzantine History at the department. The Corpus was an international encyclopedic project, based on the re-organized staff of the New Catholic Encyclopedia (published until 1967), which was housed on the campus of the University between 1967 and 1971.[2] When the enterprise fell apart, Father Dennis became a full member of the department which took over his salary which had been mostly paid by the Corpus project.

The case of Father George T. Dennis also shows how a professor of the University could follow his academic career as a famous historian of Byzantium and be an activist on- and off-campus at the same time. When he complained about the “neutrality” of the administration on questions of social injustice in his quotation for the 1971 Yearbook, he also expressed his conviction that the majority of the faculty and the students were with him in regard to social activism and the metropolitan community.

In the fall of 1970, Father Dennis was elected to head the Neighborhood Planning Council (NPC) for Northwest Washington where he lived in a small community of Jesuits. The NPC was organizing programs to help struggling youth in the area and negotiated with the DC government to improve their situation. Father Dennis jokingly declared that he preferred “to proportion his life between the Northwest Area and the Byzantine Empire.” In 1971, Father Dennis as head of the NPC, protested the declaration of a curfew in the city. Read more about Father Dennis, the NPC , and the curfew in the November 19, 1971 issue of The Tower (p.4).

On theological questions, Father Dennis came out as a “dissenter” who, in 1968 together with the theologian Charles Curran (who later left the University), publicly criticized Pope Paul VI’s Encyclical Humanae Vitae. Read more on this in The Tower, April 18, 1969 (p.10)

Later, in the mid-1980s, Father Dennis, spoke out against what he saw as the politicization of the church; he was especially critical of some bishops’ engagement in campaigns against abortion. See his September 22, 1984 letter to The Washington Post for more.

Eight years later Father Dennis criticized the founding of a library that served as predecessor to the Saint John John Paul II National Shrine, accusing him of having been “consistently hostile to genuine academic spirit and practice.” See more in the See more in the November 20, 1992 issue of The Tower (p. 6).

Father Dennis, indeed, could never have been suspicious of “neutrality” which he thought was the position of “a few administrators” of the university, as he said in 1971. But his critique of what he thought went wrong in church and society, was not his main mission. He was an active reformer who tried to help the most vulnerable members of society. When he engaged with struggling inner-city youth, he did this without revealing his own scholarly and priestly background. The teenagers he helped with their homework and with their day-to-day problems, called him simply “George”, and “he preferred it that way”, as one obituary stated.[3]

Dr Matina McGrath, who teaches at George Mason University, was a graduate student of Father Dennis. She remembers him as an “academic mentor and a dear friend.”[4] As others, Dr McGrath was impressed by his humility: “One would never know the depth of his scholarly interests or the reputation he had among his Byzantine colleagues if he just met him hurrying to class, winded from riding his bike, straightening his hair. He loved to make his undergraduate classes fun, and was pleased beyond words when he figured out how to incorporate sounds and images in his power point presentations (I can still see him smile when he told me he had lions roaring when he showed a rendering of the imperial throne with all its mechanical contraptions). Even before electronic media, he would show up to class with bits of chain mail, helmets, miniature soldiers and siege equipment to liven up the lessons on Byzantine History. Without a doubt he was one of the most popular professors in the history department at CUA.”[5]

One of his last wishes was to donate his scholarly library to the Ukrainian Catholic University of Lviv, another sign of his wide-spread interests and his giving personality.

[1] Catholic University of America ’71 Yearbook, Washington, DC: CUA Press, p. 134.

[2] Choice, February 1979, 1560.

[3] Email from Dr. Lawrence Poos, 7 July 2020.

[4] Email from Dr. Matina McGrath to author, 9 July 2020.

[5] Email from Dr. Matina McGrath to author, 9 July 2020.

Thank you for sharing this research on my favorite scholarly uncle. He was a very humble man and when congratulated or praised in any way would just smirk a tiny bit with a twinkle in his eye and say” how touching”. I can hear him now. Thank you so much for recognizing his legacy and knowledge.

Everyone should be aware of the legacy left by Father Dennis, his story inspires several generations and makes us want to evolve as human beings.