Our guest blogger is Tian Atlas Xu, who is a student worker at the University Archives and a PhD candidate in US history at the Catholic University of America. His research examines the role of white intermediaries between non-white minorities and the administrative state in turn-of-the-century United States. He has received support from various research institutions, including the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History.

A man and his tornado machine caught our attention; a trans-Pacific life story was discovered behind the scene.

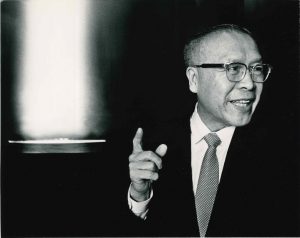

The story begins in an ordinary afternoon last winter, when my supervisor brought a dated Catholic University magazine, the Envoy, to a dimly lit back office at Aquinas Hall. As the only Asian person working in the University Archives, I was simply intrigued to see an Asian face in that magazine. The article that caught our attention was entitled “Scientist Views Change in China,” and the scientist in question was Dr. Chieh-Chien Chang, a prestigious Chinese American scholar at Catholic University in the 1960s and 70s. The publication date was February 1973, one year after President Richard Nixon’s historic visit to mainland China. It was also several months after the scientist’s first trip to his country of birth in more than two decades.

At that time, archives staff had been aware of Dr. Chang’s scientific achievements. After all, his photo with the tornado machine, a simulator of natural tornadoes to study “peculiar elements responsible for near-the-ground destruction,” has appeared in the University’s course catalogs and documentary histories since the late 1960s. We also knew he had co-founded the Space Science and Applied Physics Department at Catholic in 1963, and that he had laid the foundation of the University’s long-term partnership with NASA. According to the administrative accounts, students enjoyed his classes; and from his pictures with the tornado machine, he was clearly enjoying the passionate love affair between a lab and its creator. The 1973 article was not meant to add anything new.

But it did, in totally unexpected ways. We soon realized that Dr. Chang’s visit to China in 1972 was part of a larger-than-life moment in US-China relations: after more than two decades of intellectual blockade, it was the first time that a large number of American scientists and their colleagues in mainland China engaged in direct conversation with each other. More importantly, we discovered that Dr. Chang had witnessed many moments like this in his life. He was a village kid who carved his way into a warlord-sponsored Chinese university in Manchuria; at the age of twenty-three, he saw the mighty Japanese Imperial Army occupied his fertile but helpless motherland; he fled to Beijing with his schoolmates and, as a young lecturer in aeronautics at Tsinghua University, developed one of the first monoplanes in China with his Chinese colleagues; and in the 1940s, he became a student of Theodore von Karman, a key figure in the development of aeronautical sciences, not only in the United States, but also in the China as we know it today. The list goes on and on.

We set out to piece together his life story through documents in English and Chinese. It was the early months of the pandemic, and Covid-19 was called by all kinds of names hostile to Chinese and Chinese Americanness. The pandemic caught the trans-Pacific academic community in the middle, and a new campaign for the decoupling between Chinese and American scientists appeared on the horizon. But at the same time, the turbulent experience of Dr. Chang and his generation of Chinese American scientists beckon to us all the more.

His generation tells a story of difficult choices during the Cold War, of the damage done, not only by the revolutionary culture in China, but also by McCarthyism and xenophobia in the United States. It turns out that the tornado machine was a small piece of Cold War history, not about confrontation and fear, but about a Chinese American’s personal identity struggle and heartfelt yearning for peace: in the 1960s, Dr. Chang chose to move on from his earlier research of missiles, planes and military satellites; his attention turned towards the lives impoverished by natural disasters on the planet earth, such as tornadoes. His right to choose was profoundly American, yet his freewill bent towards love for both China and the United States.

What was initially designed as a blogpost quickly develops into an online exhibit. Our technician braved the archives to dig up nuggets of Dr. Chang’s experience at Catholic in the 1960s and 70s. The scattered memories of him in American and Chinese sources were sifted and carefully knitted to recapture a trans-Pacific life that had touched on many. Emails were exchanged between us and Dr. Chang’s alma mater, the Northeastern University of China, which, after his unwavering mediation since retirement, had restored its long-lost name in 1993. We learned about his exile with other Chinese scholars during the Second World War and the group’s forced migration from the Bohai Bay to the mountainside of Tibet; we saw his sunny smile in the early 1940s, when he stood with a group of young Chinese scientists celebrating a wartime US-China alliance at Pasadena, California. We even discovered the picture of a symposium banquet in plasma physics in 1963, right here in Washington, where Dr. Chang, a typical husband of the Second World War generation, seemed to be the only scholar to bring his wife to the occasion.

We are now sharing these details with you. The online exhibit takes you to forgotten times and unfamiliar territories, where an aspirant young engineer built his career at a time of war and national humiliation. It also provides fresh insights into the history taking place here in America, a land of opportunities that offered this Chinese American the environment to thrive while driving many others away. It confirms that, at the Catholic University of America, Dr. Chang’s transnational career came to its most prominent fruition. Correspondence from Washington, Beijing, and Taipei competed in his Pangborn Hall office, and his busy itinerary connected friends and colleagues of two continents. The exhibit does not give easy answers to scholars’ choices amidst political storms and international strife. But one thing is certain: to attract more transnational talents like Dr. C.C. Chang, America must stick to the generous principles that have inspired them to come and persuaded them to stay.

Find our new exhibit on Dr. Chang here.