Between 1910-1914, the world witnessed a true clash of the titans. On one side were the Wright Brothers and on the other was Glenn Curtis. The dispute centered on aviation patents. During this lengthy courtroom battle, a certain Dr. Albert Zahm acted as an expert witness on Curtiss’s behalf, testifying for a month. Being a pioneer of early aeronautics and long-time adviser to the Wrights, Zahm’s testimony on behalf of their rival added an additional layer of drama to the already-complicated dispute.

But let us back up a minute here. Who was Albert Zahm and what does CUA have to do with him? Not only was Zahm a CUA professor of Engineering and Mechanics from 1895-1908, he also constructed the first experimental wind tunnel in the United States on the campus, a building that still exists to this day.

Albert Zahm, like so many flight pioneers, was born in Ohio in 1862. As an undergraduate at Notre Dame, he discovered a passion for flight. Inspired by the story of Daedalus and Icarus, Zahm experimented with models, primitive wind tunnels, and even hoisting up fellow students with makeshift wings and pulleys! Upon earning his Masters at Cornell, Zahm taught mathematics at Notre Dame before coming to CUA in 1895 as a Professor of Mechanics. While teaching at CUA, he earned his doctorate in Engineering from Johns Hopkins University in 1898. While working on his dissertation research, he is alleged to have fired four-inch hollow spheres out of a small cannon in McMahon Hall, in the process developing a light measurement system for determining velocity that was instrumental in early aviation experiments.

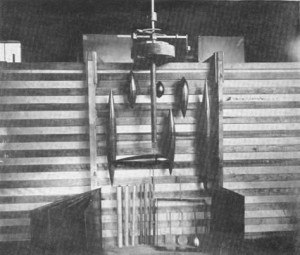

In 1901, funded by Hugo Mattullath in what is today the stucco building behind the Power Plant, a laboratory was constructed and equipped with state-of-the-art instruments for measuring air velocity and pressure. Referred to as the beloved “mechanical wizard” by his students, Zahm was said to overwork himself, “often laboring in that building until the electricity went off at ten o’clock at night.”[i] It was during this time that Zahm published the results of his research in a 1904 paper, “Atmospheric Friction.” This work revealed for the first time that skin friction is responsible for the major part of the drag on aeronautical bodies. Zahm’s experiments on campus helped establish the optimal airship hull design – the torpedo shape – that continues to exist to this day.

Despite leaving the University in 1908, Zahm continued with his work in the field of aviation. At the same time that he was serving as a controversial witness in the Patent Wars, he called for the formation of a government-endowed aeronautics laboratory. Thanks in part to his advocacy, in 1915 the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics – the spiritual precursor to NASA – was formed. From 1916-1929, Zahm served as director of the Aerodynamical Laboratory with the U.S. Navy. Then from 1929-1946, he held the Guggenheim Chair of Aeronautics at the Library of Congress, a position specifically created for him. He lived well into his late 80s, passing away in 1954, just shy of the start of the Space Age. His papers are held at the Notre Dame Archives.

One final note: Like any good tale from the early 1900s, Theodore Roosevelt has to make an appearance. Zahm happened to have an older brother, one Rev. John Zahm. John was a Holy Cross father, early Notre Dame educator and administrator, and Darwinian biologist. In 1913-1914, alongside Roosevelt, Rev. Zahm started out on an expedition to explore the River of Doubt in the Amazon Basin. While the priest eventually left the expedition once it reached the River, it was undoubtedly for the best. The remainder of the voyage would prove to be so perilous, that is almost cost the former President his life. But that is a story for another day.

[1]Kuntz, Frank. Undergraduate Days, 1904-1908 (Catholic University of America Press), 94.