Over the past year, Special Collections staff has continued addressing conservation challenges that arise within the Catholic University’s Rare Books collection. You may see our past blogs on the topic in “Part I”, “Part II”, and “Part III”. As in years past, we have continued working alongside Quarto Conservation and have another surprising sampling of works that span centuries and regions!

Our goal in Special Collections is to make sure that all of our patrons – whether they are members of the CatholicU community or visiting researchers – have access to the materials they require to satisfy their research needs. Thus, our guiding principle in conserving these books is to render them stable for both eventual digitization and in-person access, while preserving the original content and physical traits of the volumes themselves.

As we continue with our conservation efforts, we will update the community on the work being performed. You may see examples of the before and after of each conserved volume below with brief summaries of the conservation work performed:

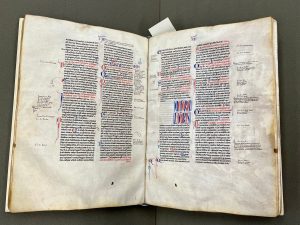

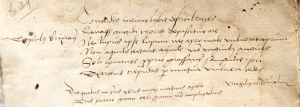

- Erasmus, In Novum Testamentum, Volumes I and II, 1524

This large, two-volume set of sixteenth-century texts, printed in 1512, is an early first-edition copy of Erasmus’s commentary on the New Testament. The binding is from a later period – the eighteenth century. Each volume faced its own conservation challenges.

The first volume had poor binding, with its front board completely detached. The back board also had worm damage, which was also exhibited in the textblock. (These are the type of holes caused by insects tunneling through a book, not to be confused with the type of wormholes that tunnel through spacetime.) Other than the worm holes, the textblock was fairly stable.

To address the issues of this volume, Quarto used a Dremel tool to drill holes through the board and textblock shoulder to reattach the board to the spine. Japanese tissue was also adhered to the spine to improve the attachment.

The second volume’s binding was also in poor condition. In this case, both front and back boards were detached, although the backboard had been loosely reattached with cloth tape. Some worm damage on the text, but not as much as in volume 1.

To address the issues with this volume, Quarto started by removing the cloth tape using methyl cellulose. Like in the first volume, a Dremel tool was used to bore holes through which a linen thread could be laced through and reattach the boards to the spine. Japanese tissue was used to further add in the attachment and repair tears in the leather binding.

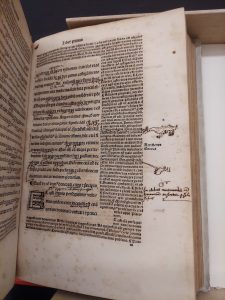

- Josephus, De Bello Judiaco, 1480 (Inc 79)

This book is an incunabulum (referring to a book printed in Europe prior to 1501), with a modern binding from the early to mid twentieth century. Unfortunately, the textblock was split in two, straight down the spine, leaving the book in two halves. Other than this grave issue, the media and text block are in excellent condition.

To start with repairing this work, the twentieth-century binding was removed. The two halves of the textblock were then lined with Japanese tissue and wheat starch paste. Once that was complete, the two halves were sewn together using linen threads pieced together through the original sewing holes. New endsheets and boards were added to the textblock.

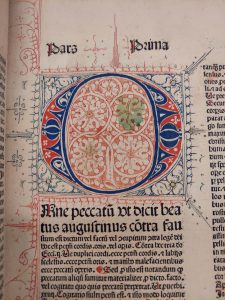

- Summa Destructionum (Inc 1)

Another incunabulum from the collections, this work’s physical qualities include a full leather binding over wooden boards. The boards appear to be original, with the spine possessing gold tooling decoration, but there is evidence of later binding work. The original text block is in excellent condition, but the binding has failed. Both wooden boards are detached, and the spine’s leather is degrading. However, the original boards and sewing are still present.

The brittle nature of the spine’s leather made it impossible to reuse, so it was removed mechanically and preserved in a Mylar sleeve. The spine was then cleaned and relined with Japanese tissue and wheat starch paste. New boards were created to avoid drilling into the original boards, and then attached with linen threads. The original boards were preserved with the returned incunabulum.

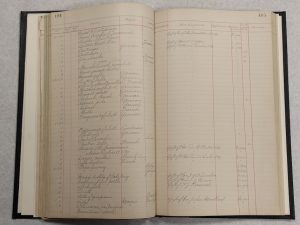

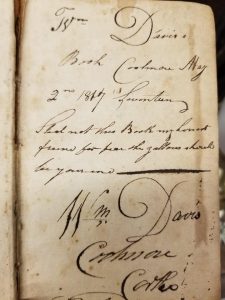

- Minutes of the Board of Trustees of the Catholic University of America, 1885-1933

Compared to the other items sent out to conservation this year, this volume may seem out of place. A commercially-made records ledger from the late nineteenth century, the book served as the official record for the meeting minutes of CatholicU’s Board of Trustees from the school’s founding until the early 1930s. Its contents were handwritten and included such records as the official acceptance of the donation money that founded the University! So while it may seem more limited in its research scope, it is one of the most prized objects in our collection, documenting the history of our home.

Before conservation, the ledger’s binding was in poor condition, with its front and back cover boards detached and original leather degrading. While the text within was in good condition, its weakened binding made it difficult to safely access.

To resolve these issues, the conservators disbound the original binding and boards and repaired the textblock with Japanese issue and wheat starch. The book was resewn with new board and archival-quality double folio endsheets were added into the text. The original boards were saved, while the textblock itself was digitized. You may access the digital files here: http://hdl.handle.net/1961/cuislandora:304001

While there are many details that this post did not address regarding the conservation efforts, we hope this sheds a little light on the process of conservation in the stacks.

To find out more about these books or the general Catholic University Rare Books collection, please contact us at: lib-rarebooks@cua.edu