Working in the Special Collections stacks, you often see messages from the past. Notes from long-past authors or readers, who have scribbled in the margins or front leaves of books. Some notes are merely the thoughts of a reader or a dedication, but at other times, there is a note directed to you – the person holding this book – a warning from centuries past. A curse!

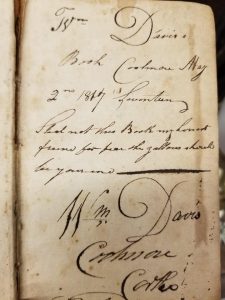

“Steal not this book my honest friend for fear the gallows should be your end”

So warns a handwritten note in a 1756 edition of The Works of Jonathan Swift. Written in the same hand as the note of its later owner, “Wm. Davis’s Book Coolmore [possibly Culmore, Ireland] May 2nd 1817…”, it stands out as one of the known curses that exist within the Catholic University rare books collection, but not a surprising find.

Modern special collections libraries have all manner of security features to protect their holdings from theft, flood, fire, and more. These protections come in many forms – from alarm systems, specialized access policies, disaster plans, etc. But one thing that is perhaps missing from today’s library is curses. A long-common practice, dating back millennia, book curses were another means by which creators and owners of books wished to protect their manuscripts. The labor-intensive process of creating books prior to the invention of the printing press made books an extremely valuable – if not vulnerable – piece of property. One could limit access to a collection or chain up the books, but why not add a final threatening note to ward off would-be miscreants?

While the curses could be written by the later owners of a book – such as is the case in early modern printed books – in the medieval period, it was often the scribes themselves who added a final warning to their texts. After spending countless hours copying a text, a scribe may have wanted to guarantee that his work would be respected and protected by adding a few lines of warning to any would-be book thieves or desecrators.

While these warnings could be simple pleas to one’s conscience, they could also call forth cruel punishments or God’s wrath (or the executioner’s rope) upon anyone who plucked or mistreated the work in question. But the spirit was the same – protect the hard labor and valuable material that constituted the book. In an age before the printing press – and even well past its widespread use in Europe – books were valuable and expensive objects that might not be easily replaced. The loss or desecration of one could snuff out a person’s only copy of a work or eradicate months (or even years) of hard work by a dedicated scribe.

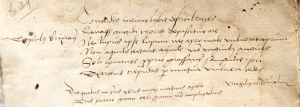

Beyond a warning from the nineteenth century in our collection, we also hold a 1460s German Passionale, a collection of martyrology narratives. This handwritten manuscript from the late medieval period is cataloged with the note that it has a “book curse” on its first folio. No further details or translation were offered, so our staff went to work. (We had to know what actions we should avoid, lest we receive the curse…)

While it still remains somewhat of a mystery to us – and we welcome additional feedback – thanks to the dedicated work of History doctoral candidate, Nick Brown, and several graduate students*, we are much closer to identifying what spell may have been placed upon our staff. Here is an approximate transcription and translation:

Concordes ineunt Lybie deserta leones,

Sevaque concordi tygris depascitur ore.

Nec lupus ipse lupum, nec aper male vulnerat aprum;

Non aquilis certant aquile, non anguibus angues.

Soli homines proprio grassantur sanguine. Soli

Exercent trepidas per mutua vulnera cedes.

Dic quibus in terris, et eris mihi magnus Apollo,

Tres pateat celi spatium non amplius ulnas?

The lions go peacefully together into the deserts of Libya,

And the fierce tiger grazes with a docile mouth.

The wolf does not harm another wolf, nor does the boar harm another boar;

Eagles do not contend with eagles, nor does the snake contend with the snake.

Only humans go after the blood of their own kind. Only they,

Through wounding each other, bring about restless murders.

Speak, and you will be great Apollo to me, in what land

Does heaven extend no more than the space of three measures?

Our working theory is that the “curse” is a later addition, and not from the original scribe. While the date of the “curse” is unclear, we are are certain that the passage is referencing two distinct sources, circulating in the late medieval/early modern period. The first is a passage on animals,”taken from De vita solitaria et civili, a collection of poems attributed to Theophilus Brixianus. There was a fifth-century bishop of Brescia by this name, but it looks like all we know about him is that he was bishop and martyr. Perhaps the “curse” author wanted to open the work with a quote attributed to an early Christian martyr, as a link to the passion narratives in the text (and on the theme of the humans shedding blood)?

The last two lines of the “curse” are from Virgil’s Eclogue III, and is called the Riddle of Damoetas. The rediscovery of Virgil is a significant theme in the early Renaissance, suggesting a familiarity with the scribe to his works. While it may not be a “curse” per se, it does open up a fascinating window into the literary diet of its author, as well as the broader social milieu under which they operated. This passage may have been written during a time of early literary humanism and classicism in the Italian and/or German sphere. As the riddle itself remains unresolved, is the scribe offering his own answer to it in the context of the example of the passion narratives? Take your own guess!

So while we cannot say for sure how many of our books are definitively cursed, we think it safe to say that we will treat all our books with the utmost respect (and caution). Not just as professional curators of these treasures, but lest some vengeful reader/writer past unleash their curse upon us!

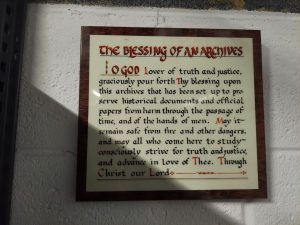

And even if our books are cursed, our reading rooms are not! In fact, they are blessed, and are open to appointments. Contact us at this link: https://libraries.catholic.edu/special-collections/archives/about/contact-us.html

*In addition to Nick Brown, special thanks to Patsy Craig, Jon Dell Isola, Jane and Luke Maschue, and Alex Audziayuk. They double-checked the translation and aided in the research of the Passionale’s “curse”.

For more information on book curses:

Drogin, Marc. Anathema: Medieval Scribes and the History of Book Curses. Totowa, NJ: Allanheld & Schram, 1983.

O’Hagan, Lauren Alex. “Steal not this book my honest friend.” Textual Cultures 13, no. 2 (Fall 2020): 244-274.

More on Virgil’s riddle: