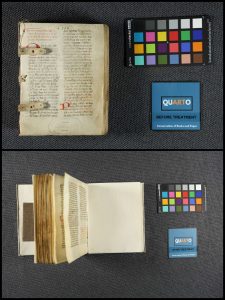

This past academic year, Special Collections staff continued our long-term project of addressing conservation issues within the Catholic University’s Rare Books collection. As “Part I” of the conservation blog post reported, we began by looking at four of our late medieval European manuscripts. While we continue to prioritize our handwritten manuscripts, this time, the date and geographic range of Quarto’s efforts varied from medieval Europe to late colonial Mexico!

Our goal in Special Collections is to provide both our external and campus patrons with access to the works they need to research and study. And thus, our number one goal in conserving these manuscripts was to render them stable for both eventual digitization and in-person access, without damaging the text or any original materials in the binding.

As this project progresses, we will continue to keep the campus community informed about the ongoing conservation work and what materials are now safe for full access! And thus, without further ado, we present the five most recently conserved works:

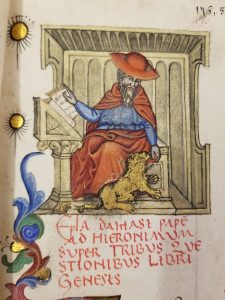

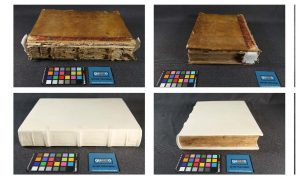

1. Quadriga Spirituale, ca. 1500, (MS 115)

This work faced real challenges with its binding. The original binding had become quite loose, with tears throughout. The conservators stabilized the binding using wheat starch and Japanese tissue. The binding was preserved and stored in a separate box with a foam insert to mimic the original textblock (the pages inside the covers and binding) and support the binding.

The endbands (the cords affixed on a book spine to provide structural support) of the textblock were stabilized, with the spine stabilized through Japanese tissue and new alum tawed (a calf leather prepared with a liquid solution to create a white appearance) sewing supports sown in. The text was covered with a handmade non-adhesive paper binding to protect the spine and text.

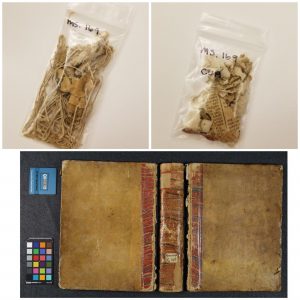

2. Instruccion del Estado del Regno de Mexico, 1794 (MS 121)

This volume lacked any binding, leaving the textblock fully exposed. The spine was loose, with tears in the page caused by abrasive iron gall ink used in the original writing. Iron gall ink was a widely used ink in European works until the nineteenth century, made of iron salts and tannic acids. The conservators worked to stabilize the spine and remove – but conserve for our records – some of the abrasive papers and glue in the spine. They cleaned, stabilized, and mended the tears caused by the ink on the first few pages of the text. A paper binding was created to cover and protect the work.

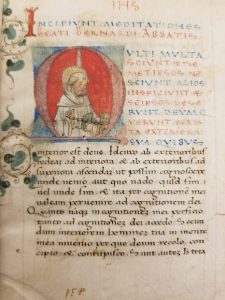

3. Meditationes Beati Bernardi Abbatis, ca. 1400 (MS 126)

The text’s binding and end cover boards (front and back) were loose, with the boards completely detached from the textblock. This binding was a nineteenth-century addition to the original text.

The conservators cleaned the spine and end boards, stabilizing them. They then carefully reattached the endsheets (blank sheets often bound at either end of a textblock to protect the text) and end boards to the textblock. Utilizing microscopic analysis, they reviewed the ink of the text to see if any stabilization was required and noted that none was currently necessary.

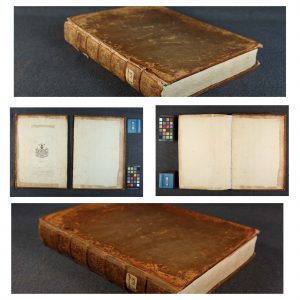

4. The interior Christian or a sure guide for those who aspire to perfection in the spiritual life, 1796 (MS 262)

The leather cover was worn along the spine, but the most grave concern about this work was that the binding and textblock was split down the middle of the spine. The work was literally falling in half, with the two halves stiff and difficult to open.

The conservators stabilized the leather front and back cover boards, as well as cleaned the interior of the text. They gently lifted the leather spine and added new sown bindings to stabilize the textblock and make it accessible to readers again. The original spine was removed and safely stored with our records, with a new paper spine created to cover the binding.

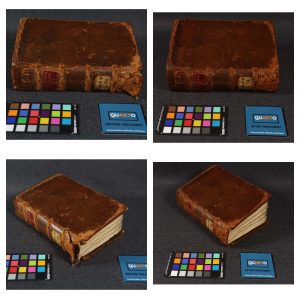

5. Theologiae polemicae, 1733 (MS 264)

This work’s leather cover was heavily damaged through red rot. The spine of the cover had completely disintegrated over the years, leaving the threads of the binding exposed. However, the threads were heavily compromised, offering no support to the text and thus rendering the pages loose. Some damage was noted along the pages that had been in close contact with the leather binding. The binding is original to the text, but was so damaged that it needed to be replaced (but with the threads and cover boards kept).

The conservators unbound the text and carefully paginated the pages to maintain proper order. The spine was cleaned and tears throughout the text mended with Japanese tissue and wheat starch paste. The textblock was resewn, with new endsheets added to protect the original pages. A historically similar binding with boards was created to protect the text.

To find out more about these books or the general Catholic University Rare Books collection, please contact us at: lib-rarebooks@cua.edu

Our digitized manuscripts may also be viewed at this link.