On the night of October 30, 1938, a startling message went across the airwaves of America: “Ladies and gentlemen, I have a grave announcement to make. Incredible as it may seem, both the observations of science and the evidence of our eyes lead to the inescapable assumption that those strange beings who landed in the Jersey farmlands tonight are the vanguard of an invading army from the planet Mars.”

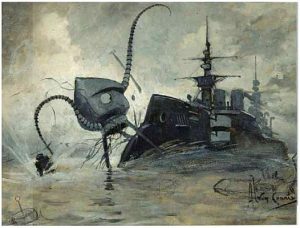

Adapted from H.G. Wells’s War of the Worlds, this Orson Welles radio drama stirred up quite the reaction in a nation worried about war and disaster. The infamy of this broadcast can be seen in the various headlines that followed on Halloween, 1938. Tales of a panic-stricken nation, mass evacuations and hospitalizations, and armed gangs hunting alien invaders are splashed across newspapers across the nation (and world). This broadcast not only has become a legend, but it staked out Welles as a master of dramatic adaptations.

Of course, the reports of mass hysteria have recently been questioned (see here and here), with the media hype playing more of a role in defining the legend than the actual response by listeners. Nevertheless, at the time of the broadcast, there is no doubt that many people were entertained and enjoyed the tension and terror the radio drama provided. There are even some people who had a bit of fun with the idea of a “Martian hoard” descending upon the nation.

For while it makes a good Halloween tale to imagine residents of Washington worried that they may soon be facing the aliens and their horrible tripod machines, we should remember that others did not give into fear but prepared to make a tongue-in-cheek stand against the “Monsters of Mars.” As reported by the Tower war correspondent, Paul Eldridge ’39, Catholic University students allegedly waged a pitched battle against the Martians.

In the broadcast, the military called on all observatories to watch Mars for further ships being launched. Unfortunately, Catholic University lacked the means to assist in this national scouting mission, with the campus observatory having been lost over a decade prior. Built in 1890, the Observatory burned down, coincidentally, on Halloween night, 1924. (The remainder of the telescope base can still be seen outside of Aquinas Hall today.) Without this warning system, Eldridge reports, the advance of Martian scouts into the Brookland neighborhood took the campus community by surprise. Fortunately, the Martians were distracted by “10 double-fudge sundaes” at a local diner. This gave the students enough time to mount a defensive perimeter, with the rear guard strategically placing themselves out of sight and “under each bed.”

With civilians evacuated to the chapel, Mr. Eldridge reports that the student defenders rallied and mounted several defenses. They mined the halls of campus buildings with mousetraps, located skates to create a mobile infantry, and erected barricades, constructed of “[l]ogic, history, Latin and Greek textbooks…because these were hard to get through.”

Fortunately, the invasion was swiftly ended, as the one-hour mark of the broadcast arrived. Despite the valiant efforts of the “Grand Army of Catholic University,” the invasion from Mars was ultimately halted by Earth’s bacteria (or the end of the broadcast). Welles informs us that the Martians were “slain, after all man’s defenses had failed, by the humblest thing that God in His wisdom put upon this earth.” In the mocking report that Eldridge issued, he reveals a student body both prepared to defend its campus and willing to laugh at itself.

Study this example well, for you never know if the Martians may return someday…