The following is a selection from Catholic University student Annaliese Haman’s class paper on a piece of Renaissance-era Italian art held by Special Collections at the University. Ms. Haman’s piece was submitted as an assignment for Professor Tiffany Hunt’s course ART 272: The Cosmopolitan Renaissance and edited by Special Collection’s Dr. Maria Mazzenga. The students used art from the University collections for their papers.

When choosing a piece to research from the Catholic University Archives’ collection, I did not know where to begin. Certain pieces, such as the antique furniture, held a certain mystery and intrigue about them; they were also unique. The few triptychs available were of immediate interest as I have a fondness for altarpieces. However, I wanted to research something simple and fairly straightforward, so I looked at the few paintings available in the collection.

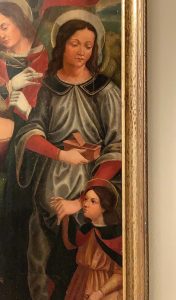

The Madonna with Child, Saints, and Angels oil painting on wood (Fig. 1) caught my attention, firstly because of its proximity to my dormitory. Having easy access to this piece immediately was a bonus. Yet as I examined the piece further, it continued to grow in its benefits. The piece needs restoration, but even with its cracks and damage, it was in very good condition and seemed worth pursuing for my projects.

Going to the Catholic University Archives for my designated research time sparked many interesting thoughts. I was glad that the archives did indeed have files on my piece. Though much of my file consisted of inventory records, there was a great deal of substance on the provenance of this painting. It originally belonged to Jeane Dixon. Dixon was a rather interesting character. She was born in 1904, and she was a devout Roman Catholic and a prophet. This was self-described but was attested to by many people around her. Her supposed psychic abilities garnered her fame and fortune. Dixon resided in Washington D.C. with her husband, who was involved in real estate and automobiles. She had many friends in high places and most importantly with respect to this painting, she was a friend of Monsignor James Magner, an administrator at Catholic University and a collector of art and historical objects. Magner donated much of his collection to the University’s Special Collections.

Ruth Montgomery’s book, A Gift of Prophecy: The Phenomenal Jeane Dixon A Gift of Prophecy: The Phenomenal Jeane Dixon notes that Dixon first saw Madonna with Child, Saints, and Angels at the 1939-40 World’s Fair. The painting later showed up in Washington, D.C. where Dixon saw it again.[1] This time, she bought the piece. She held on to it for many years, though it was kept at a friend’s house. When she began looking to donate it, Msgr. Magner leaped at the opportunity to acquire it. She agreed to donate the painting to Catholic University in her husband’s name and honor. [2] This new object of the university was a great point of pride: “Catholic University was so proud of its acquisition that it later exhibited the painting on a television program and reproduced its likeness on the school’s official Christmas cards.”[3]

Both Montgomery’s book and correspondence in the archives note the acquisition of the painting. The book notes the supposed artist of the piece for the first time: “Innocenzo da Imola’s sixteenth-century painting of the Madonna and Child in a nativity scene…” This tells us that when Dixon purchased the painting, the artist’s identity was known.[4]

Many inventory documents support Innocenzo as the artist. He was Italian, living between 1490 and 1545, and he worked primarily in Bologna, though he did spend some time in Florence.[5] His work shows this Florentine influence through his formation of composition. According to Oxford Art Online, many of Innocenzo’s works were focused on the Madonna and Child with varied saints. This painting seems to fit right in with his known repertoire. It is unknown where the initial connection to him was made; there is no signature that can be seen in the present day; perhaps it was visible in 1939-40, but no known documentation exists confirming this. How Innocenzo became connected to this piece is missing from the provenance.

One document in the archives contains an appraisal. Here we get a name for the piece, The Madonna with Child, Saints and Angels. It is rather generic for a work of art, but many Renaissance pieces followed this type of structure of a Madonna and Child in a nativity scene surrounded by either the shepherds or various saints depending on the purpose of the painting. This appraisal helps provide many details about the piece, and gives weight to Imola’s name. “If it is, indeed, a work of Imola, it is an important find.”[6] This appraisal also notes the date of the gift, the Summer of 1956.

A 2016 letter from Christopher Daly to Archives staff member, Katherine Santa Ana, and Art Department professor, Dr. Nora Heimann, provides a great deal of previously unknown information on the painting. He references the piece as, Nativity with Saint Genesius, Saint Blaise, a Young Martyr, and the Archangel Raphael with Tobias. The three previously unidentified saints and angels are named. Their attributes are easily visible, so it is not too difficult to figure out who they are. Having a firm statement of their identities is a great addition to our knowledge of the piece.

What is most interesting about Daly’s letter is his bold claim that Innocenzo is not the artist. “As mentioned, I believe the painting is a characteristic work by Ranieri di Leonardo, formerly known as ‘The Master of the Crocefisso dei Bianchi.’”[7] Daly proceeds to give some information about Ranieri, namely, that he was Pisan and active in Lucca between 1502 and 1521.[8] In his letter, Daly explains how he connected this Nativity with Ranieri. “Although CUA’s painting is heavily repainted, the composition and stiffly-posed figure types as well as some morphological details, such as the round, fleshy faces and the bony fingers, are legible…” which he connected to Ranieri’s work.[9]

Daly wrote and published a chapter in the book Filippino Lippi: Beauty, Invention and Intelligence. Daly’s chapter is titled Filippino Lippi: Reconsidering Lucchese Painting after Filippino. What is most beneficial about this chapter is that many other paintings by Ranieri are given as examples in this chapter on Lucchese school painting. These paintings help to solidify this Virgin and Child as an Italian painting. The two attributed artists do strongly support its Italian origins, but having substantial examples of other Italian paintings from the same school helps to provide a greater understanding of how this painting fits into the style and techniques of its time. Daly gives a summary description of the painting before explaining how he connected this piece to Ranieri when it had been attributed to Innocenzo da Imola.

Not only are Ranieri’s characteristic bloated and restrained figure types clearly visible through the altarpiece’s heavily repainted surface, its unusual iconography – with a group of saints flanking a Nativity group rather than the customary Virgin and Child – allows it to be identified with the ‘Nascita di nostro Signore con l’arcangelo Raffaele e altri Santi,’ commissioned from Ranieri by the operai of San Tommaso in Pelleria, Lucca, on 26 March 1510.[10]

In his research on this piece, Daly was able to find the contract that connected it to Ranieri. The reason this piece has connections to the Church is that the Church had a chapel dedicated to St. Genesius. The Church had also previously contracted Ranieri to create another altarpiece. Contracts hold keys to discovering many of the intricacies of Renaissance paintings. They can explain the globalization of the works, along with the localization. Yet within that localization, there can still be found aspects of the globalization of the cultures of the time.

This painting was commissioned by an Italian church to an Italian artist. And to further limit the scope of this painting, it was a church local to the artist. And yet this supposed limitation does not mean the painting does not exhibit the globalization of the world. Looking at the fabrics in the piece, little details in their patterns come out. Saint Raphael (Fig. 2) has a subtle pattern of little golden dots on his clothes. His collar also sports this gilding. Yet these are not the grand patterns and designs of the Netherlandish painters. In fact, these clothes are in a contemporary style.

The setting of this nativity is not the traditional setting of Bethlehem. As the Renaissance progressed, artists began using more and more motifs and settings that placed scenes and saints in the contemporary world. Though there are only two slim windows of viewing, a lovely green countryside can be seen in the background, behind Saint Genesius and Saint Raphael respectively. Part of this countryside can be seen in Figure 2. There is also the climbing vine along the front entrance of the stable. It could possibly be native or live in Bethlehem and the surrounding areas, but it is much more likely that this was a vine native to Italy, and possibly the Lucca region specifically. That stable also has much more of an Italian style to it than something built in ancient Judea. The round arch and the smooth walls without any indication of stonework or woodwork appear to be stucco.

At this point is it worth noting that Daly commented that this painting had been repainted and reworked.[11] These details could have been added later, to achieve this same effect of bringing the Holy Family and the Nativity to Italy. This possibility cannot be fully answered without an x-ray look at the painting and a more detailed study by experts. And yet this painting exhibits a beautiful and traditional scene that shows how the Renaissance and its artists recognized the importance of seeing day-to-day settings in the context of important events. And how fitting that this piece would be found at a World’s Fair, a modern example of the great global exchange that the Renaissance began in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

Notes:

[1] Ruth Montgomery, A Gift of Prophecy: The Phenomenal Jeane Dixon (New York: Bantam Books, 1965), 137. [2] Montgomery, Gift of Prophecy, 138. [3] Montgomery, Gift of Prophecy, 139. [4] Montgomery, Gift of Prophecy, 137. [5] Any information about Innocenzo da Imola comes from The Getty website and Oxford Art Online. [6] Unknown author, inventory document from approximately 1981. [7] Christopher Daly, “Letter to Ms. Katherine C. Santa Ana and Dr. Nora Heimann,” (letter, collection of The Catholic University of America Archives, 2016). [8] Daly, “Letter to Santa Ana and Heimann,” 2016. [9] Daly, “Letter to Santa Ana and Heimann,” 2016. [10] Christopher Daly, “Filippino Lippi: Reconsidering Lucchese Painting after Filippino,” in Filippino Lippi: Beauty, Invention and Intelligence, ed. Paula Nuttall, Geoffrey Nuttall, and Michael Kwakkelstein, (Leiden: Brill, 2020), 316. [11] Daly, “Letter to Santa Ana and Heimann,” 2016.

Bibliography

Daly, Christopher. “Letter to Ms. Katherine C. Santa Ana and Dr. Nora Heimann.” Letter, Collection of The Catholic University of America Archives, 2016.

Daly, Christopher. “Filippino Lippi: Reconsidering Lucchese Painting after Filippino.” In Filippino Lippi: Beauty, Invention and Intelligence, edited by Paula Nuttall, Geoffrey Nuttall, and Michael Kwakkelstein. 297-321. Leiden: Brill, 2020.

Montgomery, Ruth, A Gift of Prophecy: The Phenomenal Jeane Dixon. New York: Bantam Books, 1965.