Encountering a book once owned, signed, or inscribed by a distinguished person, is in some way encountering the person who signed it or closing the distance to only “a few handshakes away”. Holding the very same volume, read by someone we admire, turning the same pages, can become a transformative and inspirational experience.

Encountering a book once owned, signed, or inscribed by a distinguished person, is in some way encountering the person who signed it or closing the distance to only “a few handshakes away”. Holding the very same volume, read by someone we admire, turning the same pages, can become a transformative and inspirational experience.

Books such as these are known as association copies, and they have always been of interest to scholars and researchers providing invaluable insight into the life and acquaintances of the person who owned them. Whether they come with a bookplate or personalized inscription to their friends or colleagues, handwritten notes in the margins (aka marginalia), funny doodles scribbled within, a business card with a note, a dried flower, or a newspaper clipping folded between the pages: anything can become a source of new information.

Sometimes, people will ask us if we have any books in our Rare Books collections marked by distinguished names, and we are proud to say that we have some! W. B. Yeats, John Donne, Margaret Mitchell, Jelly Roll Morton, Dorothy Day, and Thomas Merton, to name just a few, are among those whose handwriting can be found in books on our shelves.

Until recently, if someone asked us about Tolkien (not an unreasonable question, given J.R.R. Tolkien’s strong Catholic faith and literary influence) we would have had to admit that unfortunately, we were not aware of any such books in our holdings, but now we gladly say that yes we do, though it depends on which Tolkien you have in mind, the father or the son.

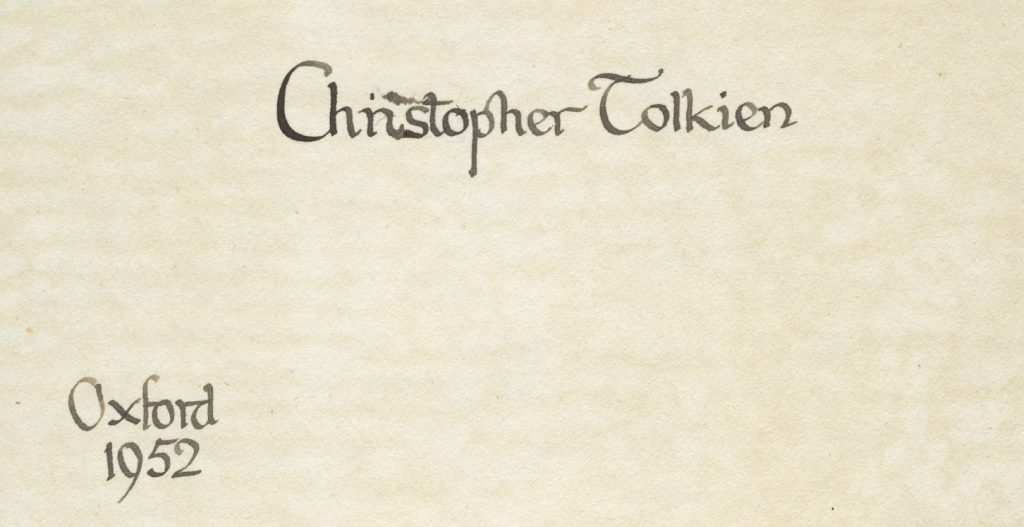

Recently, our staff member re-discovered a book in the stacks, which made some other staff members very excited once they saw on the free front endpaper the name of a previous owner:

“Christopher Tolkien,

Oxford, 1952”

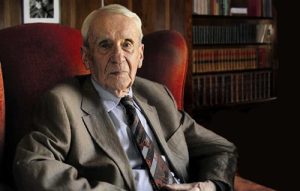

Christopher Tolkien was the youngest son of the famous writer and creator of Middle-earth J.R.R. Tolkien, who assisted in and later continued his father’s work as an editor and literary executor of his entire legacy, which became his full-time occupation and ended his over 10-year-long academic career as a Fellow of New College, Oxford. Since 1975, he was working hard to make a large corpus of J.R.R. Tolkien’s world and mythology available to readers, starting with the Silmarillion and the twelve volumes of the History of Middle-earth. His deeply scholarly work, performed with a tremendous level of understanding and attention to detail, and ability to navigate through multiple (sometimes conflicting) versions of the same narratives, compiling them into one consistent tale, makes him a most highly regarded figure for all Tolkien scholars and enthusiasts.

In 2016, for his “editorial work on his father’s manuscripts” and his “academic career at the University of Oxford”, Christopher Tolkien was awarded the highest honor of the Bodleian Libraries – the Bodley Medal.

Approaching the third anniversary of his passing on January 16, 2020, we would like to highlight the recently discovered book, associated with him, but first – to share a few stories which can provide a context to what we can see in our copy.

In the Foreword to the 50th-anniversary edition of the Hobbit in 1987, Christopher Tolkien included the recollections by his older brother Michael about the days when their father read them aloud the first draft of what would later become known as the Hobbit:

“He also remembered that I (then between four and five years old) was greatly concerned with petty consistency as the story unfolded, and that on one occasion I interrupted: ‘Last time, you said Bilbo’s front door was blue, and you said Thorin had a gold tassel on his hood, but you’ve just said that Bilbo’s front door was green, and the tassel on Thorin’s hood was silver’; at which point my father muttered ‘Damn the boy,’ and then ‘strode across the room’ to his desk to make a note.” (C. Tolkien, vii)

Some years later, when Christopher was 14, his father even paid him a twopence for every error spotted in galley-proofs of his books. (J.R.R. Tolkien, 28)

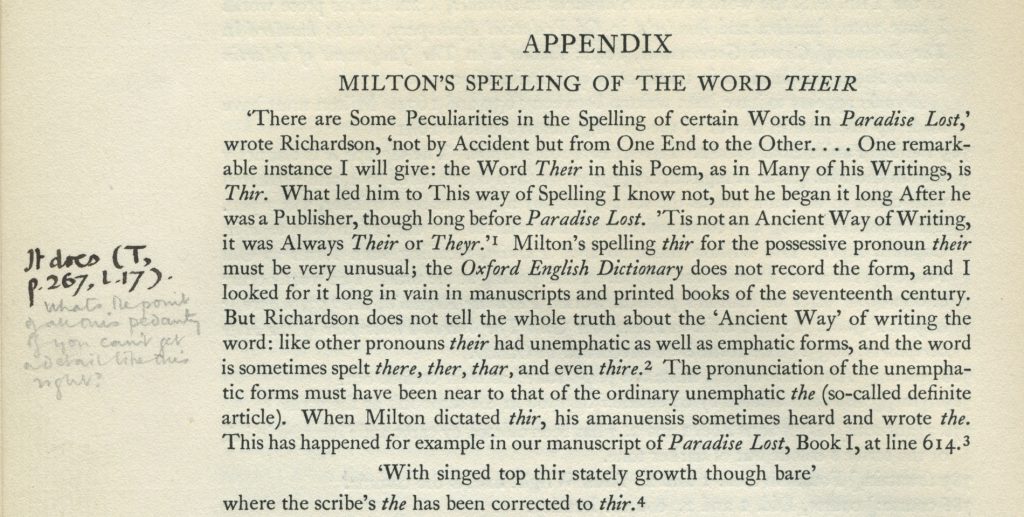

The book re-discovered in our collections is a copy of The manuscript of Milton’s Paradise lost (ed. by H. Darbishire, Oxford, 1931) once owned by Christopher Tolkien, who was then only 28 years old. It was later owned and donated to the University Libraries by Robert T. Meyer, former professor of Celtic and comparative philology at Catholic University.

In addition to Christopher Tolkien’s ownership mark, executed in brown ink in an elegant and easily recognizable penmanship that mirrors his father’s, our copy also contains a marginal note, executed in the similar ink, which allows us to assume that our copy was not just owned, but read and worked with.

Similar to how it was in the case of his childhood story mentioned above, this note is nothing else but a correction of an error, spotted by his meticulous eye. Next to the editor’s statement that “the Oxford English Dictionary does not record the form [of a certain word]”, Christopher Tolkien left a brief but precise two-word note “It does” and provided a reference.

He, probably, didn’t get any credit for spotting this error, not even his usual twopence, but for us, even this little note can tell a story.

References:

Tolkien, J. R. R., et al. The letters of J.R.R. Tolkien : a selection. Houghton Mifflin Co., 2000.

Tolkien, Christopher. Foreword. The hobbit or there and back again, by J.R.R. Tolkien, Unwin Hyman, 1987, pp. i-xvi.