The desire to form communities and act together is inherent in people. This can encompass various aspects of our lives: work, family, sport, recreation, and, of course, faith and spiritual life, which may be manifested not only through affiliation with a specific church or denomination but also through a local community of people who, sharing their faith, are also willing to share their external life of prayer and service. The term most commonly and fittingly used to describe this is “parish”, which originates from the Greek word meaning “a sojourner” or “a neighbor” [1].

The desire to form communities and act together is inherent in people. This can encompass various aspects of our lives: work, family, sport, recreation, and, of course, faith and spiritual life, which may be manifested not only through affiliation with a specific church or denomination but also through a local community of people who, sharing their faith, are also willing to share their external life of prayer and service. The term most commonly and fittingly used to describe this is “parish”, which originates from the Greek word meaning “a sojourner” or “a neighbor” [1].

Parish histories is a unique genre of publications that document and commemorate the history of such communities, and also offer insights into the lives and personal stories of its members: the places they lived, the streets they walked, the churches they built or worshiped and served in, the ceremonies they held, the schools they attended, the ministries they offered to their neighbors, and even the businesses they owned or advertised. Such publications were typically created to mark a significant event in the community’s life, would it be a dedication of a new church or school building, a visit by a distinguished person, or a jubilee of any kind, either silver (the 25th), golden (the 50th), and diamond (the 60th) anniversaries, or all the way up to the centennial (the 100th), sesquicentennial (the 150th), and beyond.

Parish histories is a unique genre of publications that document and commemorate the history of such communities, and also offer insights into the lives and personal stories of its members: the places they lived, the streets they walked, the churches they built or worshiped and served in, the ceremonies they held, the schools they attended, the ministries they offered to their neighbors, and even the businesses they owned or advertised. Such publications were typically created to mark a significant event in the community’s life, would it be a dedication of a new church or school building, a visit by a distinguished person, or a jubilee of any kind, either silver (the 25th), golden (the 50th), and diamond (the 60th) anniversaries, or all the way up to the centennial (the 100th), sesquicentennial (the 150th), and beyond.

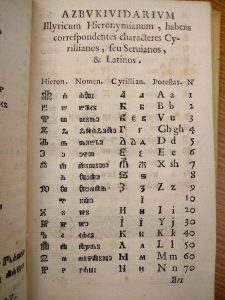

The complex nature and unique circumstances of American Catholic history have given rise to a variety of parish types. These include territorial parishes, the most common type established for Roman Catholics residing within specific geographical boundaries defined by the local diocese, national parishes, formed for individuals sharing the same nationality, culture, or language (such as Polish, German, Irish communities, and more), Black parishes, established in response to racial tensions and segregation in the country, and the so-called Eastern Rite parishes, set up for Catholics who belong to other liturgical traditions than Roman, such as Byzantine (or Ruthenian), Ukrainian, Syro-Malabar and Syro-Malankara rites (originating from India), and more. Each type of parish reflects a unique facet of the Catholic American experience, demonstrating the diversity and adaptability of the Church in different contexts.

The complex nature and unique circumstances of American Catholic history have given rise to a variety of parish types. These include territorial parishes, the most common type established for Roman Catholics residing within specific geographical boundaries defined by the local diocese, national parishes, formed for individuals sharing the same nationality, culture, or language (such as Polish, German, Irish communities, and more), Black parishes, established in response to racial tensions and segregation in the country, and the so-called Eastern Rite parishes, set up for Catholics who belong to other liturgical traditions than Roman, such as Byzantine (or Ruthenian), Ukrainian, Syro-Malabar and Syro-Malankara rites (originating from India), and more. Each type of parish reflects a unique facet of the Catholic American experience, demonstrating the diversity and adaptability of the Church in different contexts.

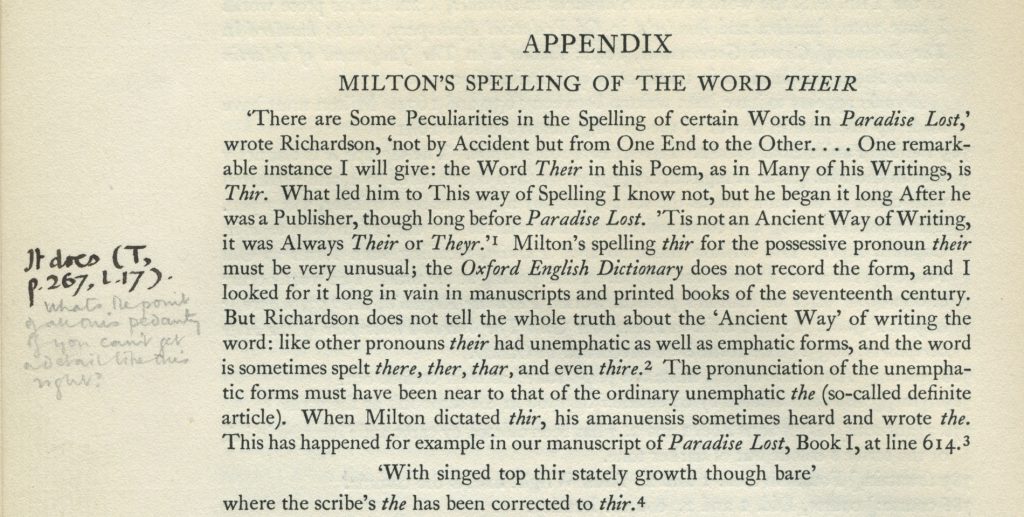

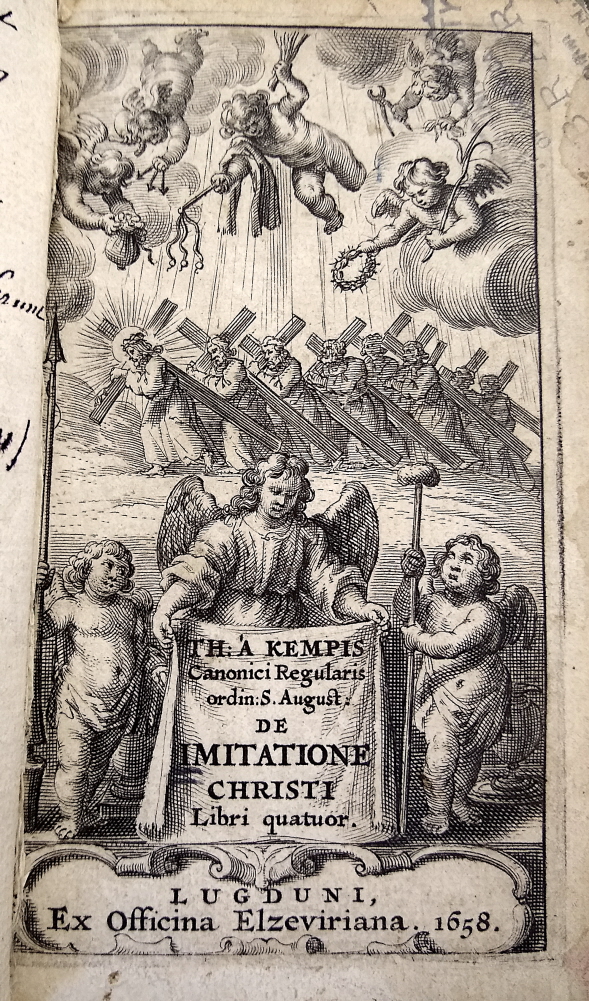

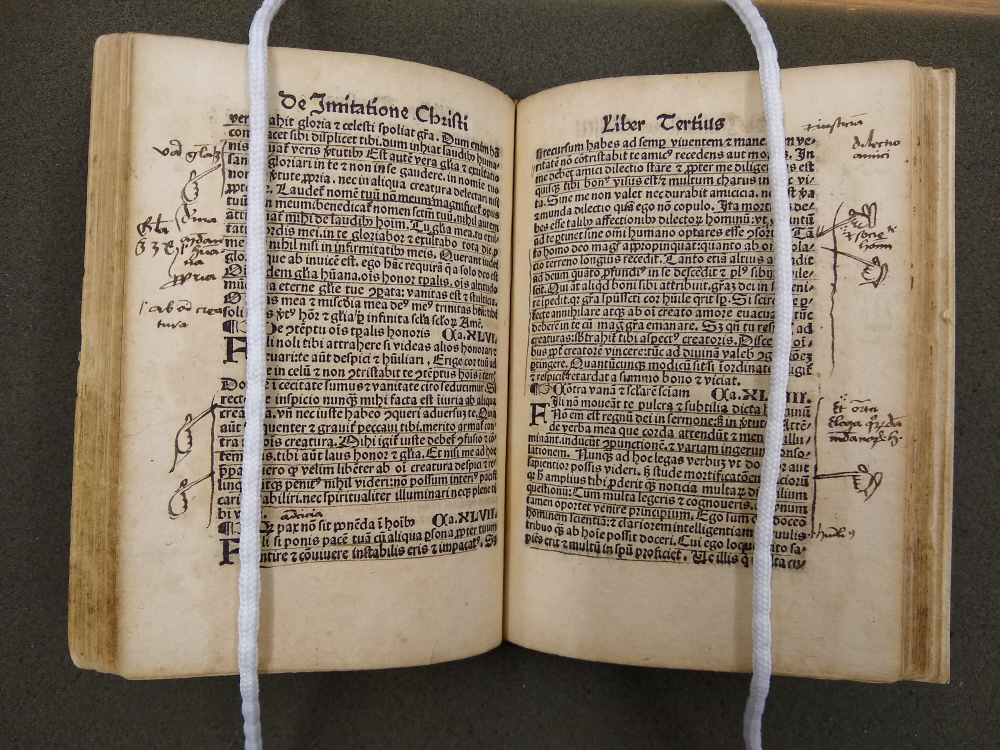

Documenting the history of all such groups, parish histories may offer unique information that can contribute to the history of the community at large. They frequently include general historical data about the neighborhood, town, or county, provide a broader context for their life in terms of language and culture, and are often accompanied by sketches, artworks, or photographs.

Images of streets and public events, the exteriors and interiors of parish buildings, group or individual photos or brief biographies of active community members, and narratives with details that may not be recorded elsewhere, can all be found within the pages of Parish Histories. As such, they serve as a valuable resource for people interested in genealogical research, as well as researchers studying local history from various angles: social, political, religious, ethnic, racial, gender, etc.

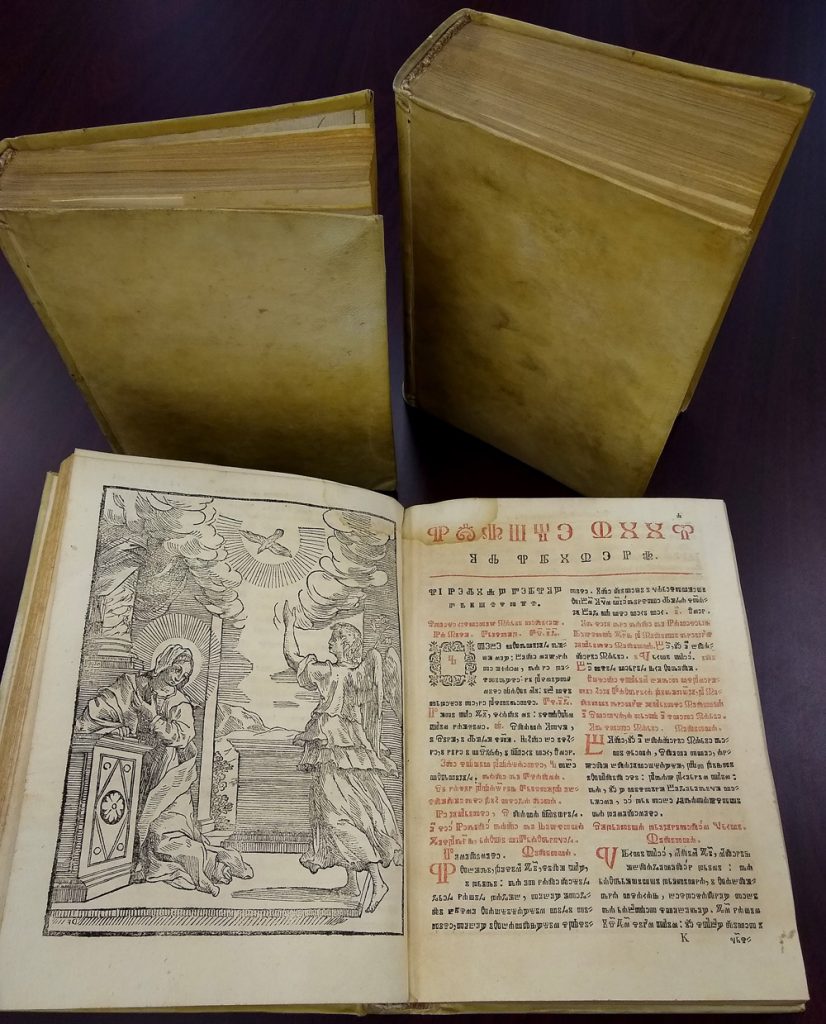

At the Catholic University of America Special Collections, we recognize and deeply value the historical significance of Parish Histories. We are also aware of how ephemeral and elusive such publications can be, and how their importance can be amplified when considered collectively rather than individually. Our American Catholic Parish Histories collection, housed in the Rare Books section, is the outcome of our commitment to actively gather, meticulously preserve, and gladly provide access to these unique publications that reflect the history of local communities and the stories of the people who built them.

Geographically, our collection encompasses all the States nationwide, and, topically, it includes the histories of dioceses, religious houses, and church ministries, parish schools and missions, and we are committed to ensuring their preservation and accessibility. Currently, we have amassed over 3,700 publications, but the collection is far from complete, with the representation of some states or dioceses being better than others. We strive to proactively collect and even occasionally purchase Parish Histories, but historically, donations have been the primary source of our collection’s growth.

Such donations, whether they come from individuals, families, or directly from parishes (who sometimes send us their newly published histories while celebrating another milestone in their life), as well as more substantial contributions from book collectors who wanted to find a good home for their treasures and believed that we can provide good care and access [2], greatly enhance our collection. When agreed upon and accepted, these contributions are deeply appreciated [3].

You can explore our Parish Histories collection through the online Database and see a few digitized samples in Rare Books Digital Collections. If you have further questions or want to schedule an appointment with Rare Books to access any of our wonderful Parish Histories in person, you can contact us at lib-rarebooks@cua.edu.

[1] https://www.etymonline.com/word/parish

[2] It’s only fitting to acknowledge here the most recent donation of 19 histories of parishes in Indiana and Connecticut published between 1903 and the 2000s. This generous contribution was made by Dr. Joseph M. White, a retired associate professor of American History from our very own Catholic University. We deeply appreciate his gift, as well as the gifts from all our donors!

[3] Those contemplating enhancing our collection through donations are encouraged to familiarize themselves with our acquisition and donation policies and reach out to us at lib-rarebooks@cua.edu before proceeding further in the process.