Nineteen-thirty-eight was not an auspicious year as far as the stability of Europe went. Adolph Hitler’s invasion into non-German territories proceeded at an alarming rate. Benito Mussolini had been running Fascist Italy as a police state for over a decade. The Vatican held uneasy diplomatic relations with both powers. Further east, Josef Stalin presided over a Soviet Union unfriendly toward religion. In short, expansionism and totalitarianism appeared to be consuming Europe and, of course, a war would begin the following year to ensure it didn’t.

The year also marked the Golden Jubilee of the Catholic University of America, which is a fancy Catholic way of saying the University turned 50. Worried about the fate of Europe and, indeed, of Catholicism, Pope Pius took advantage of the University’s 50th birthday to make a request. “Christian doctrine and Christian morality are under attack from all quarters,” he said, adding, “dangerous theories which a few years ago were but whispered in conventicles of discontent are today preached from the housetops and are even finding their way into action.” As the representative educational institution of the American hierarchy, the Pope noted, the University was endowed with the “traditional mission of guarding the natural and supernatural heritage of man.” Toward fulfillment of that mission, wrote the Pope, “it must, because of the exigencies of the present age, give special attention to the sciences of civics, sociology, and economics” in a “constructive program of social action” that fit local needs.¹

Following the Pope’s directive, the Bishops instructed the University to prepare materials of instruction in citizenship and Christian social living for use in the Catholic schools of the United States. The Commission on American Citizenship was organized in 1939 to carry out the Bishops’ mandate. They decided that the Commission would outline a statement of Christian principles as requested by the bishops, create a curriculum for the elementary schools, and oversee the writing of a series of textbooks to embody the social message of Christ. According to Dr. Mary Synon, who oversaw much of the day-to-day operation of the Commission, while the Department of Education and the School of Social Science did much of the Commission’s work, practically every department and school of the University contributed significantly.

One product of this effort was a series of textbooks for elementary through high school students used in most U.S. Catholic schools from the 1940s through the 1970s. For Catholic school students from the first through eighth grades, the Commission designed the Faith and Freedom series of basal readers based on the principles espoused in the curriculum. Aiming to establish Christian principles in the minds of students toward their use in daily living, the writers of the readers–Sister Mary Marguerite for the Primary Grades and Sister Mary Thomas Aquinas, Sister Mary Charlotte and Dr. Mary Synon for the intermediate and upper grades–built a series on social education according to the principles cited as base for the work of the Commission.

According to a 1946 Commission report, these readers were used in more than 6,000 of the 8,000 Catholic elementary schools in more than thirty-five archdioceses and dioceses in the United States. Copies of texts in this series were officially requested by the military authorities who were revising systems of education in occupied Japan and Germany after World War II. Catholic publicists in Belgium, France and the Netherlands referred to this series for their future education plans. Missionaries in the Philippines requested the copies for children there, and nearly every Catholic school in Hawaii used the texts. Also, the Commission received many inquiries from educators about using the series as possible models for books to be used in non-Catholic schools. A key theme throughout the readers is cooperation across cultures and social classes and an emphasis on Christian democratic ideals in creating a less conflicted postwar world.

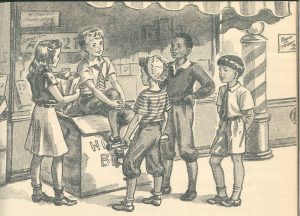

Which brings us to the significance of one 1943 text story titled “Eddie Patterson’s Friends.” Eddie was an extremely generous and open-minded young man who “finds the queerest people,” according to his rather judgmental sister Mary. Mary worried about Eddie’s strange friends with his birthday party coming up. The girls on the block where they lived would “laugh if we let Eddie ask anyone he wants to the party.” Mary went so far as to convince their mother to throw Eddie a surprise party for which she and her sister would control the guest list to keep out those she felt should be excluded.

Who were the excluded? “The smiling Yim Kee, whose father ran the Chinese laundry… Frank Bell, the boy whose father had been taken away by the police.” And, “Silas Jefferson, whose father worked as porter on a train.”² Clearly these are stereotypes of Chinese Americans, African Americans and a neglected and possibly impoverished child. But consider the year of publication: 1943. The Chinese Exclusion Act passed in 1882 barred Chinese immigrants from citizenship until it was repealed in 1943. African Americans were legally segregated from whites, and in fact segregated virtually everywhere in the U.S. Stories like this one pointed to the end of such practices and customs.

A Finding Aid to the Commission on American Citizenship records can be found here: http://archives.lib.cua.edu/findingaid/americancit.cfm

¹Maria Mazzenga, “More Democracy, More Religion: Baltimore’s Schools, Religious Pluralism, and the Second World War,” in One Hundred Years of Catholic Education: Historical Essays in Honor of the Centennial of the National Catholic Educational Association (National Catholic Education Association, 2003); Finding aid to the Commission on American Citizenship Records: http://archives.lib.cua.edu/findingaid/americancit.cfm.

²“Eddie Patterson’s Friend,” from These Are Our People by Sister M. Thomas Aquinas, O.P., M.A. and Mary Synon (Ginn and Company, 1943), 44-56, 46.