The following post was authored by Graduate Library Professional Juan-Pablo Gonzalez.

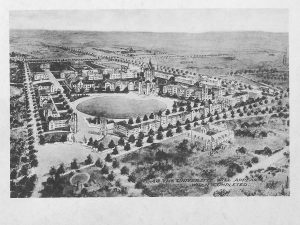

The construction of a Brutalist building at The Catholic University of America marked a departure from the existing architectural style previously seen at CUA and it was a departure from original conceptions of the growth of the university taking shape in a form that resembled a medieval village.

How did this shift in architecture challenge the ideas of public space? Was it a social experiment that was well suited to the academic environment?

I recently chatted with Eric Jenkins, a Professor of Architecture at Catholic University’s School of Architecture and Planning to get the answer to this question:

“It was very expressionist; a lot of architects in the 70s were not concerned with making a typical campus, such as Yale, with its unified and orderly sense of space; they were concerned with making a modern statement” This modernist statement was invoked in the form of Aquinas Hall, the current home of The Catholic University of America Archives and 1 of 4 Brutalist expressions currently on campus.

Washingtonians are organically familiar with the Brutalist Aesthetic, due to the ubiquity of Government Brutalism in Washington D.C. In fact, The District is home to extremely beautiful examples of the Brutalist architectural style. From the trip to work, to the work place itself, a Washingtonian’s daily routine is saturated by the atmospheric essence of Béton Brut, which can be seen in the ceilings of the Metro’s cavernous stations and seen deep within the bowels of Downtown.

Washington’s Brutalist buildings are a communique of power, impenetrability, and the performative use of materials to create a remarkable psycho-social demarcation through jarring exaggerations in building scale that coerce the viewer to process the architectural form from a macroscopic perspective, in what Professor Jenkins noted as “object-oriented landscaping, in which the building becomes a landscape object.”

Brutalism was the Federal Government’s de rigueur style during the 1970s; but tucked away at The Catholic University of America, a new player entered the field, in the form of a quieter, more pensive expression that emerged in divergent transition to the Federal Government’s translation of the Brutalist aesthetic.

In 1965, candidates for the Master of Arts in English, at The Catholic University of America, were asked during their comprehensive examinations to ruminate on a complexly layered observation made by Mark Shorer in the foreword of Society and Self in the Novel, a 1955 treatise edited by Shorer in which he made the following annunciation:

“…the problem of the novel has always been to distinguish between these two, the self and society, and at the same time to find suitable structures that will present them together.”

From an interdisciplinary standpoint, the ontological consideration of the parallels, partitions and implications of what is real, what is imagined, and what can become, is one of the core considerations of designing a building—in other words: how to reconcile between anthropocentricity and design aesthetics to create a unified conversation between these aspects that are at times in harmonious communication and at other times in discordant miscommunication. The design of CUA’s Aquinas Hall squares this circle because the building was not designed through a psycho-social lens but rather as a form of psycho-geographical praxis in which scale is downplayed and the viewer’s gaze is shifted to the granular level. In this context, the juxtaposition of raw, coarse, unpolished, imperfect, cacophonous materiality results in theatric, unexpected geometries.

A melodic, psychogeographic exploration of the geometry and materiality of the Brutalist home of The Catholic University of America’s Archives.

Images and video of Aquinas Hall are by the author, Juan-Pablo Gonzalez.

Brutalism is jarring and upsetting to the soul. It dehumanizes; it’s an assault. I used to think that Aquinas was simply weird and therefore worthy of toleration; now I know that it was deliberately designed that way and so I cannot enjoy its idiosyncracy.

From the 1977 dedication of the then-Boys Town Center (later renamed Aquinas Hall): “While architectural aesthetics were an important part of the construction synthesis, the two prime considerations were work-efficient interiors, and energy-conscious innovations. Floor space and offices were planned for interdepartmental access and operation efficiency. Temperature change controls…result in lower energy use in unoccupied portions of the building. Heavily cantilevered upper-levels functionally shade the front terraces in the path of the sun, while the sheer rise of the structure at the rear seems to complement the fall-away of the hillside on which the building rests.”

Think of the chaotic beauty of a Basquiat piece–it’s something that demands more when interacting with it. It refuses to be beautiful in the expected ways and it defines beauty on its own terms, which the viewer is forced to reconcile . In that same manner, the darkness of Brutalism is poetic and beautiful. So I agree with Deacon Nicholas. The edifice: its shapes, its dimensions, and its materials, have all intersected to demand something more. They challenge the pedestrian nature of interactions in public space. The work has specific sentiments and senses imagined by its artist. For that to come to fruition, validates this form of architecture as significant and has proven it to be performative. Shouldn’t architecture demand something of us beyond acting as stale, unimaginative containers? Architecture is an art form and by extension a tool of sociology and of psychology; however, what you mentioned is specific to and elemental of State Brutalism. Campus Brutalism creatives socio-emotional stimulation for the scholarly community. This is seen in the design of Aquinas and how it evokes a contemplative energy. The building is not only the home of the archives, it also houses the Mathematics and Philosophy department, which are fields that would definitely find the building to be an interesting art work. .