November 9-10 of this month marks the 80th anniversary of Kristallnacht, also known as the “night of broken glass.” The Kristallnacht pogrom against Jews by German Stormtroopers and German civilians took place across Germany in 1938, and is often viewed as the beginning of the Holocaust for its escalation of Jewish social and political persecution into overt physical brutality. More than one thousand synagogues and Jewish businesses were destroyed, at least 91 Jews were killed, and 30,000 Jewish men were arrested and sent to concentration camps. The pogrom was condemned by many around the world, from politicians to representatives of all faiths. U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt summoned home the American ambassador to Germany as a sign of U.S. disgust, saying he “could scarcely believe that such things could occur in a twentieth-century civilization.”

Not all Americans were critical of the Nazis’ activities against Jews. The German American Bund, for example, was a pro-Nazi organization established in the U.S. in 1936. More than 20,000 people attended a pro-Nazi rally organized by Bund leader Fritz Kuhn in February, 1939. Among Catholics, Father Charles Coughlin, the “radio priest,” was an anti-Semitic supporter of Nazi Germany with many millions of followers in the late 1930s. Anti-Judaism was, in fact, widespread in the United States at the time.

Generally speaking, American Catholics were not known for coming to the defense of Jews in the U.S. in the 1930s, though the two religious groups could certainly sympathize with each other given that both anti-Catholicism and anti-Jewish sentiment were quite widespread in the U.S. at the time.

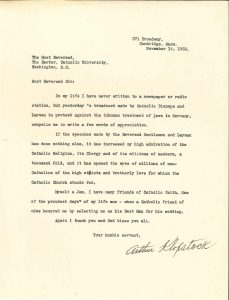

In fact, Archives staff were surprised about a decade ago to find a damaged album labeled “Catholic Protest Against the Nazis—November 16, 1938.” The album was badly damaged and the audio could only be retrieved by employing a sound specialist, which we did, in 2007. The recording turned out to be a 27-minute condemnation of the Nazi actions against the Jews during Kristallnacht by several American Catholic bishops, the rector of Catholic University, and a former Democratic presidential candidate. The broadcast took place a week after the pogrom, with both CBS and NBS networks carrying it across the United States, and The New York Times reprinting its text on its front page. Now we know that while Coughlin’s anti-Semitism existed and flourished in the 1930s, there was also another group of Catholics, including several members of the Catholic hierarchy, who found the actions of the Nazis toward the Jews reprehensible and stated it publicly.

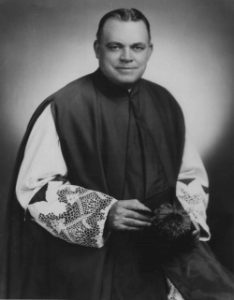

The Broadcast was organized by Father Maurice Sheehy, Assistant Professor in the Department of Religious Education at Catholic University and assistant to the Catholic University rector. Sheehy was an adept organizer who managed the university radio station, possessed many contacts within the church, in the Washington, D.C. community, and in national politics. Sheehy was joined in the broadcast by Archbishop John J. Mitty of San Francisco, California; Bishop John M. Gannon of Erie, Pennsylvania; Bishop Peter L. Ireton of Richmond, Virginia; former Democratic Presidential Candidate and Governor of New York, Alfred E. Smith, and Catholic University Rector, Monsignor Joseph M. Corrigan. The participants were selected to represent both lay Catholics (hence Smith’s inclusion) and clerical leaders’ unified view that the violence unleashed on Jews and Jewish property in Germany was immoral, contrary to Christian teaching and against American ideals of religious and civic freedom. They also compared the treatment of the Jews by the Germans to the persecutions of Catholics in Spain and Mexico.

Four days later, Father Charles Coughlin, the hugely popular Catholic “radio priest” from Michigan, went on the air to deliver a broadcast titled “Persecution – Jewish and Christian.” Claiming he would add his voice to those protesting the Nazi pogrom against Germany’s Jewish population of several days earlier, Coughlin instead offered a justification of the Nazi persecutions as a natural defense against an alleged Jewish-dominated communist movement. Coughlin also mocked the Catholic University-sponsored address of Archbishop John J. Mitty, referring to him sarcastically as the “Most intellectual Archbishop” and suggesting that the Catholic University broadcast participants cared more about the persecution of Jews than the welfare of Catholics.

The reactions to both broadcasts was substantial and intense, with hundreds of stories appearing in the media on each. The American Catholic History Classroom explores the broadcast, Coughlin’s response, and other documents here.

Excellent scholarship and writing; I learned much I hadn’t known.

I enjoyed the piece on Catholics and Kristallnacht. Another voice condemning the violence was then Archbishop Samuel A Stritch of Milwaukee (later archbishop and cardinal of Chicago). Stritch’s words, picked up by the public press, elicited a warm commendation from MIlwaukee’s leading rabbi, Joseph Barron.

Likewise, Milwaukee priest and future archdiocesan historian Father (later Msgr.) Peter Leo Johnson served as a chaplain in France. He left behind a remarkable body of letters home describing in details the realities of life “over there.”