This week’s post is guest-authored by Mikkaela Bailey is a PhD student at CUA studying medieval history with special interests in women’s history, public history, and digital humanities. You can find her on Twitter: @mikkaela_bailey

Curation is a long, detailed conversation between individuals, offices, texts, and objects, as students from Catholic University’s History and Public Life class learned this semester.

It’s easy to evaluate an exhibit and poke holes in the choices made by its organizers. It’s far more difficult than I imagined to craft an exhibit.

With most of the logistics arranged long in advance by our professor for the class History and Public Life, Dr. Maria Mazzenga, our job as a class was focused on assembling and advertising the physical exhibit itself.

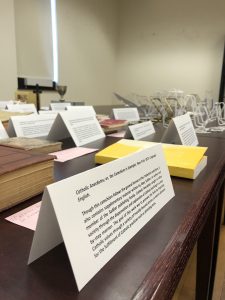

The first thing we had to do was break up the objects into thematic categories so we could decide what should be included in our display. Then, we had to plan how to best demonstrate the common themes between them and also establish continuity in the display. After that, we had to craft captions and marketing materials that communicated why our visitors should care about our work and choose to come see it.

One of the ideas about organizing the books rested on the idea that the Eucharist is a central and essential element of the catechism and one’s first Communion is an important life event. Since our audience is likely to be heavily Catholic, there is resonance with their own experiences in the exhibit here. This thematic approach connected well with the objects in the exhibit, and inspiration flowed from that idea as we assembled catechisms aimed at children and teens in the same display case. One thematic element of change over time was the implementation of more children’s catechetical education as the age for first Communion shifted from around 13 to around 7 years of age.

But, there were still two more cases to fill and many more objects to consider. In the first case, which we actually finished last, we installed the oldest books, including a Latin catechism from 1566. These 16th and 18th century books were connected by the vernacular languages in which they were printed. Printing educational materials in the vernacular was a very important emphasis of the Tridentine Catechisms, so grouping these non-English catechisms gave emphasis to the importance of the catechism worldwide, outside our own framework, and outside the Latin-based world of the church.

The central case features several interesting pieces, but it also provides context for the cases flanking it. This is where we chose to place the bulk of our textual engagement through questions we are asking the audience and a QR code linked to the digital exhibit.

At the end of this process, I am so thankful for teammates who were engaged from the beginning and expressed great passion for this project. I shudder to think of undertaking something like this alone! In fact, looking at the finished product, I feel as though no idea I had for the display was totally my own and I think almost every decision made was by committee. From the marketing materials to the captions and display case arrangements, this exhibit was completely collaborative and has benefitted from open communication and easy acceptance of constructive criticism. In public history, I think all of these qualities are essential for a successful, cohesive exhibit. This experience has been the highlight of my first semester as a PhD student at CUA!