About a month after the United States entered the Second World War, The Young Catholic Messenger, a weekly magazine that could be found on the shelves of Catholic school libraries throughout the country, published an article titled “United We Stand.” The article pledged that Catholics would support the war effort and outlined ways young people could “do their part for victory.” Catholic youth could make “crusades of prayer, sacrifice, Masses and Communions for victory and peace and for our soldiers and the leaders of the country.”¹

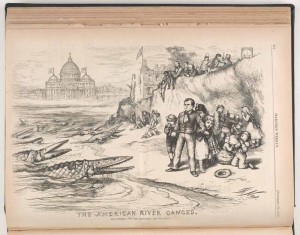

This braiding of Catholicism and Americanism occurred over and over again among youth on the home front. It marked a break from the past in that earlier Catholic proclamations of Americanness were often made defensively, amid Protestant accusations that Catholics weren’t fit for American institutions because of their membership in a hierarchical organization headed by the pope. Instead, during the war, a newly confident Catholic Americanism emerged in Catholic educational institutions and popular culture across the country as Catholics were fully enlisted in the effort to win the war.²

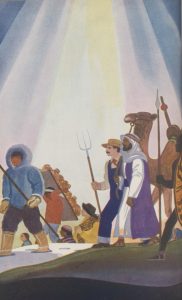

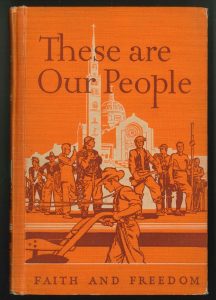

As noted in a previous blog post, Pope Pius XI requested that the Catholic University of America establish a series of educational materials that would promote Christian and democratic principles in the wake of rising totalitarian regimes in Europe. The result was the Commission on American Citizenship, which established a series of civic texts blending Catholic teaching and democratic principles and used in thousands of Catholic schools across the country from the early 1940s through the 1970s. This blending of American national identity with Catholic identity found new forms across the U.S. during the Second World War.

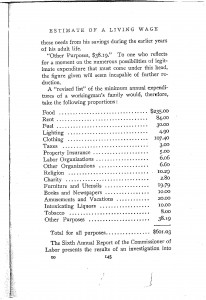

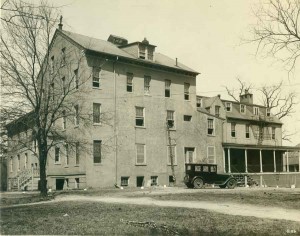

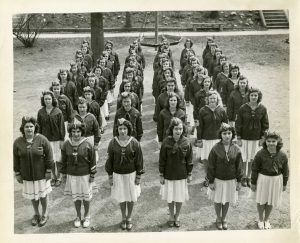

St. Rose’s Technical School records contain a gem of an artifact related to this new blending of Catholicism and Americanism in youth culture that is a fitting offering for Pearl Harbor Day. St. Rose’s was established in 1868 for female orphans. After 1895 it was incorporated as school for female students over 14 years of age to learn trades considered suitable for women at the time, namely, “plain and fancy sewing, dressmaking, and the responsible duties of practical housekeeping.” Between the late nineteenth and the early twentieth centuries, the young women remained at the school until they were twenty-one, “at which time they are thoroughly competent to make an honest independent living.” Indeed, one history noted, “our graduates make splendid business women, and they conduct large establishments in all the large cities.”³

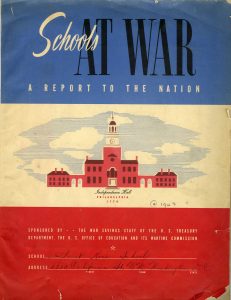

Unfortunately, we do not have testimony from the students of St. Rose’s to corroborate such claims. We do know that a classical and business high school curriculum was added to the “technical” curriculum of the earlier period.⁴ And we have a student created journal from 1943, a full year into the Second World War. “Schools at War, A Report to the Nation” was a report on war-related student activities that took place in the school during the war. The report reflects the characteristic blending of Catholicism and Americanism we see among young Catholics on the home front during the war.

The report itself was dedicated to the “Immaculate Mother of God, the Patroness of the United States, the Ideal and Inspiration of every student at St. Rose.” The St. Rose Victory Corps centered many activities around war service. Like many Americans, they prolonged use of their clothing by mending and darning. They saved scrap materials such as old keys, cans, rubber and fat—all in short supply due to war rationing. Like many American youth, they made slippers and bandages for soldiers, donated blood, and collected garments for refugees. Using the title, “Books are Weapons,” they created a school display for National Catholic Book Week, claiming “books shape lives of free people,” no doubt to contrast with Nazi book burnings of the 1930s. The report and its wartime brand of Catholic Americanism can be viewed in its entirety here.

¹Young Catholic Messenger, January 9, 1942, accessible via American Catholic History Research Center and University Archives: http://cuislandora.wrlc.org/islandora/object/achc-ycm%3A23/datastream/PDF/view

²Maria Mazzenga, “More Democracy, More Religion, Baltimore’s Schools, Religious Pluralism and the Second World War,” in One Hundred Years of Catholic Education, John Augenstein, Christopher J. Kauffman, Robert J. Wister, eds. (National Catholic Education Association, 2003), 199-219.

³Sister Rose, “St. Rose’s Technical School History,” 1909, 14; in Catholic Charities DC, St. Rose Reference File, American Catholic History Research Center and University Archives, Catholic University, Washington, D.C.

⁴“Saint Rose to Observe 75th Jubilee,” Catholic Review, April 30, 1943.