This week’s post is guest-authored by Ronnie Georgieff, a graduate student in Library and Information Science at Catholic University.

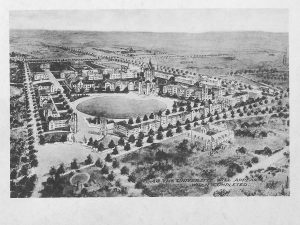

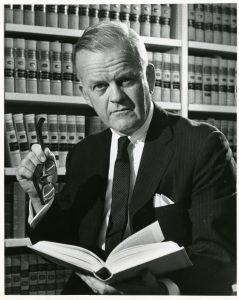

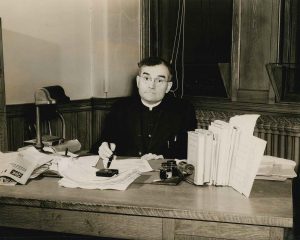

Monsignor James Marshall Campbell devoted his life to The Catholic University of America (CUA) as a student, professor in the Greek and Latin Department, Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, his contributions shaped the lives of many. His collection is comprised of 8 boxes that consist of research notes, sermons, homilies, lecture notes, articles, course outlines, photographs, newspaper clippings, correspondence and prayer books.

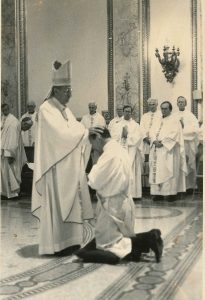

Campbell was born on September 30, 1895 in Warsaw N.Y., and was educated at Hamilton College (1913-1917) to receive his B.A. in Greek, Princeton University (1917-1918), and then The Catholic University of America (1920-1923) where he received his M.A and Ph.D. in Greek. He prepared for the priesthood at the Sulpician Seminary, now the Theological College, and was ordained on January 14, 1926. He was a brilliant academic, who had a particular love for the classics. He became a professional assistant in the classics (1920-1921), then an instructor (1921-1927), an associate professor of Greek civilization (1927-1932) and finally a professor of Greek (1932). He was fluent in English, Attic Greek, Latin, German, and French, and his professional studies included advanced Attic Greek composition, ancient Greek tragedy, Greek philosophy, ancient history, history of classical philosophy and Greek fathers. In addition, he was a member of Phi Beta Kappa, the American Philological Association, and the Medieval Academy of America. His research and teaching material reflected his scholarly passion, writing several books, articles, and contributions. Most notably, he wrote his master thesis on ‘The Question of the Origins of Tragedy’ (1920), wrote his doctoral thesis on ‘The Influence of the Second Sophistic on the Style of the Sermons of St. Basil’ (1922), ‘The Greek Fathers’ (1929), ‘The Confessions of St. Augustine: Books I-X’ (1931), A Concordance of Prudentius’ (1928-9), and ‘Los Padres Giegos’ (1948).

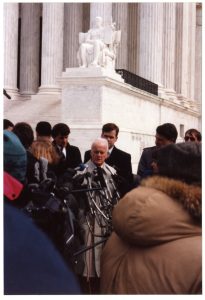

Campbell served as the Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences (1934) until he retired (1966). He was also the Director of the Pacific Coast Branch of the Summer Session (1932-1970), helped develop a plan of concentration for the curriculum which is partially modeled off the Princeton preceptorial system, and even cut out football at Catholic University as an intercollegiate sport. This was not the only grievance that he caused, and a number of academic controversies created a rift between the College of Arts and Sciences faculty and Campbell. There was even a walkout in February of 1966 and it was soon followed by a petition for the replacement of the Dean in March 1966. As a priest and later a monsignor, he was a chaplain at Holy Cross Academy and Dumbarton College while simultaneously working at CUA. He was also named a Domestic Prelate of His Holiness Pope John XXIII (1959). He died the evening of March 25, 1977 at St. Joseph’s Home of the Little Sisters of the Poor.

It was not until I processed this collection as part of a library science practicum that I learned about Msgr. Campbell and his contributions to CUA. His passion in academia as well as his administrative leadership showcase a remarkable individual who through both his small and large contributions is an inspiration to follow your passion and lead with excellence. See the Msgr. James Marshall Campbell finding aid.